By John N. Pearce, February 2024

Tim Wilson (10th April 1943 – 10th Sept 2017).

Tim Wilson will be terribly missed by all his family and friends, and those on Facebook and Twitter who encountered his wit and wisdom, love of The Blues, and unremitting support for the NHS.

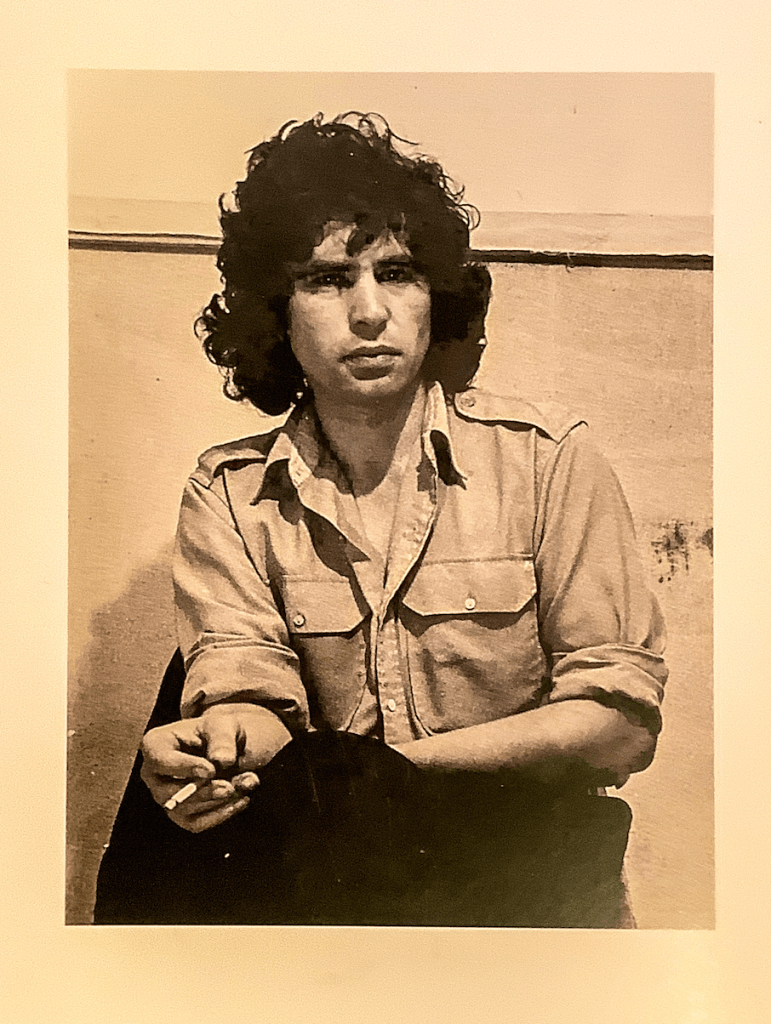

One of his grandchildren described him as ‘the funniest man in the world’. A working colleague said he was ‘the world’s most inoffensive person’. His appearance over the years changed little, with his hair growing down to his collar – unremarkable now, but in the 1960s it could arouse police suspicion: When he and his wife Janet lost their way en-route to their honeymoon destination in Hastings, they were stopped and questioned by police and spent their wedding night in a police cell. With his typically downbeat hmour, Tim could certainly see the funny side.

His many friends will each have their own memories. I was certainly not his closest friend, but he meant a lot to me both as an artist and as a human being; someone who was as amusing as he was serious, yet who sometimes didn’t take himself quite seriously enough. That’s my personal view, so this is a personal memoir.

Tim and I belonged to the first post-war age-groups not to be called up for National Service, and at Art College were less mature in years and experience than male students of previous years’ intake. In addition, ours was the last year-group studying for the N.D.D. (National Diploma in Design) which was about to be replaced with the Dip. A.D. (Diploma in Art and Design). Caught between avant-guard and traditional priorities, and with a more mixed and less upper-class range of students than in some art colleges, Hornsey tutors seemed worried lest Hornsey fail to meet the new standards.

The uncertainty and contradictory approaches of the college staff (who ranged from Jesse Cast, a former pupil of Henry Tonks, to the youthful Bridget Riley, soon to be a sixties icon) did little to calm our own confusion, and in the painting school it seemed a case of sink or swim – maybe not always a bad thing, yet some of the most outstanding talents failed the N.D.D.

Tim’s characteristic downbeat honesty and a very human sense of existential bewilderment, not unmingled with wit, humour, and a sharp eye and ear for pretentiousness, served him well. To his credit, he admitted he found painting incredibly difficult. He worked hard, but as the examination approached, Tim confided to me that no tutor had actually spoken to him in the entire year! He gained his N.D.D. nevertheless.

Tim was all too modest about his abilities, but his questioning, self-critical attitute was also a strength, and he was a talented draughtsman.

He was also extremely musical with a taste for directness and simplicity of expression rather than heroic grandeur. At art college, he was not only a fan of the blues, but also fascinated by Alfred Deller and the renewed exploration of 16th & 17th C English church music. Tim was particularly moved by The Deller Consort’s recording of ‘The Record of John’. He thought the depth of feeling in Orlando Gibbons’ setting of the Biblical text, culminating in ‘I am the voice of one that crieth in the wilderness…’ remained musically unsurpassed. But , as a Jazz trumpeter himself, he was generally more at home with improvised performance, and particularly The Blues.

It was and is characteristic of art students to be ‘into everything’. Tim was no exception. At one stage he discovered the works of the Victorian poet William McGonagall and tape-recorded himself reading such epics as ‘The Tay Bridge Disaster’, to lugubrious, hilarious effect – and with no attempt at a Scottish accent.

I lost contact with Tim and most of my Hornsey associates in the early 1970s, only to rediscover them in 1997 when one of my teaching colleagues in Tottenham turned out to be the brother in law of another Hornsey alumnus, the painter Gerry Keon. Attending a private view at one of Gerry’s exhibitions, I at once recognised Tim’s characteristic laugh – loud, infectious and unchanged over the years.

In those intervening years, after pursuing various employments, including working in a Christmas tree factory and a spell of school teaching, Tim had found work in the art workshop of Oddbins in Clerkenwell. When in the late l980s Oddbins ceased having hand-painted shop-fronts, the small group of artists continued to take commissions as freelance sign-painters, achieving particular recognition for their decoration of the bridge at Camden Lock in 1989, and when one of Tim’s designs won the 1990 Hillier Parker Hoarding of the Year prize.

They also worked on film sets, and Tim produced artwork for The Borrowers (1997), the James Bond film The World Is Not Enough (1999), and in Harry Potter films, on which he worked with another Hornsey contemporary, the set designer Stuart Craig. Besides his own painting. Tim also continued as a freelance painter of commissioned pictures, signs, and decorative pieces,

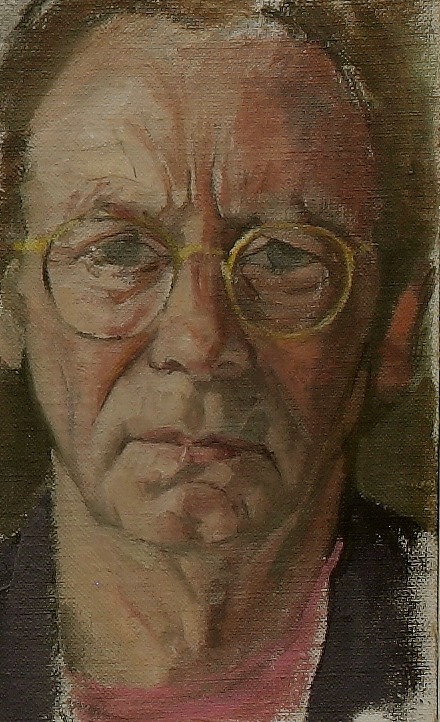

Tim’s ‘Old Contemporaries’ exhibits included a series of self-portrait studies remarkable for their candid objectivity. His artistic statement for the exhibition was also characteristic:

‘I went to Hornsey Art School at 16 years of age knowing nothing about art. I always felt that there were secrets to which I was not privy. I just wanted to paint. Artists had “something to say” – I just wanted to mutter quietly to myself.’

Christopher Chapman (1943 – 2023).

John Parsons has written the following memoir of Chris:

“Dear Chris – now so sadly missed. He was such a calm, kind and quiet man. I first met him in the late fifties at Hornsey Art School. How green we all were in those days, although he had a slight advantage with a father who ran the school in that beautiful village of Much Hadham, he was a mini star!

We all milled around in room F, as complete strangers. Chris’s hair stood out for me. Art School in many ways was the making of us. Chris also stood out as someone who could draw very well, even at that early stage. A skill that he developed to a fine degree, his draftsmanship was always truly amazing.

He soon took up lodgings in Miranda Road Archway, where a whole network of our mutual friends lived. In those days it was quite a scene, relationships, sounds and parties, with Chris as cool as ever. We were often at Royal College dances, I took the whole gang in one of my old bangers, Chris’s head seemed to tower over all those would be stars at the hop.

During lunch breaks at the Art School we would often retire to the Queens Head for half a pint and a game of bar billiards, I think he often won because he had longer arms and was taller.

My strongest memory, is that he always stood out as kind and gentle, on top of his good looks that is. I remember taking him and Mary Moore to Eel Pie Island in order to listen to the Yardbirds, and while crossing the bridge, staring into the Thames, thinking about the great adventure that lay ahead of us.

His great skill at drawing and knowledge of colour stood him well, and so dear Chris, if Heaven does exist, you’ll no doubt be up there, with a paint brush and pen.

May God bless you dear brother, and friend. With love

John.”

‘Mary Moore’, whom John Parsons mentions, was daughter of the sculptor Henry Moore. Christopher and she were at that time accepted as ‘an item’.

Despite what Parsons says regarding Christopher’s artistic talents – which were considerable, his work having been successfully promoted in some major galleries in the UK and abroad – things did not come easily. Most of those who knew Chris would probably attest to his seriousness, hesitancy and circumspection before making any sort of statement – let alone with the permanence of paint on canvas.

In the context of the ‘Old Contemporaries’ Exhibition, Chris wrote the following:

“Painting is the most demanding thing I know. It is difficult, elusive and the variables involved appear to be infinite. When things go well it can be satisfying and, briefly, fulfilling. At other times it can be frustrating and seem completely futile. There is no rational explanation for continuing with it. Like others I know I have stopped, occasionally for considerable periods of time, but I always seem to be ineluctably drawn back to it, as if some gravitational pull were at work”

After graduating from Art College, Chris taught for a time in the art department at Edith Cavell School, where he was appreciated both for his artistic ability and his quiet and patient approach to the more difficult children. He subsequently won an open scholarship to pursue his painting development in Italy, and after that prolonged his education still further by taking degrees in ‘Arch and Ant’ (Archeology and Anthropology) and History of Art at Cambridge University.

At the same time Chris taught life-drawing at an evening class. One of his pupils, another Cambridge undergraduate – whom we only know as “Harriet” – recalls “Christopher was an interesting teacher, darkly mysterious, hovering discreetly behind our boards, sensitive as to how much or how little he should intrude, careful with comments. Chris was not a bossy personality performer…instead he was humble but assured, intense but self-effacing – an artist philosopher…”

J. N. P.

.